C++ standard limitations and Persistent Memory

Introduction

C++ language restrictions and the persistent memory programming paradigm imply serious restrictions on objects which may be stored on persistent medium. A user can access persistent memory with memory mapped files to take advantage of its byte addressability thanks to libpmemobj and Storage Networking Industry Association non-volatile memory programming model. No serialization takes place here, thus applications must be able to read and modify directly from the medium even after application was closed and reopened or after the event of power loss.

What does the above mean from the C++ and libpmemobj’s perspective? There are four major problems which will be described in this blogpost:

- Object lifetime

- Snapshotting objects in transactions

- Fixed on-media layout of stored objects

- Pointers as object members

Object lifetime

The lifetime of an object is described in [basic.life] section in the C++ standard:

The lifetime of an object or reference is a runtime property of the object or reference. A variable is said to have vacuous initialization if it is default-initialized and, if it is of class type or a (possibly multi-dimensional) array thereof, that class type has a trivial default constructor. The lifetime of an object of type T begins when:

(1.1) storage with the proper alignment and size for type T is obtained, and

(1.2) its initialization (if any) is complete (including vacuous initialization) ([dcl.init]), except that if the object is a union member or subobject thereof, its lifetime only begins if that union member is the initialized member in the union ([dcl.init.aggr], [class.base.init]), or as described in [class.union].

The lifetime of an object o of type T ends when:

(1.3) if T is a non-class type, the object is destroyed, or

(1.4) if T is a class type, the destructor call starts, or

(1.5) the storage which the object occupies is released, or is reused by an object that is not nested within o ([intro.object]).

The standard states that properties ascribed to objects apply for a given object only during its lifetime. In this context, persistent memory programming problem is similar to transmitting data over a network where the C++ application is given an array of bytes but might be able to recognize the type of object sent. However, the object was not constructed in this application so using it would result in undefined behavior. This problem is well known and is being addressed by WG21 (The C++ Standards Committee Working Group).

Currently there is no possible way to overcome object’s lifetime obstacle and stop relying on undefined behavior from C++ standard’s point of view. libpmemobj++ bindings are tested and validated with various C++11 complaint compilers and use case scenarios and the only recommendation for libpmemobj C++ users is that they must keep in mind this limitation when designing their persistent memory application.

Trivial types

Transactions are the heart of libpmemobj. That is why libpmemobj++ was implemented

with utmost care while designing their C++ versions, so that they are as easy to use as possible.

It means that the user doesn’t have to know about implementation details and doesn’t have

to care about snapshotting modified data in order to make undo-log based transaction works. A

special semi-transparent template property class pmem::obj::p<> has been implemented to automatically add

variable modifications to the transaction undo log.

But what does it mean to snapshot the data? The answer is very simple, but the

consequences for C++ are serious. libpmemobj implements snapshotting by copying data of

given length from given address to another address with memcpy(). If transaction aborts

or the event of power loss occurs, the data is being copied again from undo log on pool reopen.

Consider a definition of the following C++ object and think about the consequences

of memcpying it:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

class nonTriviallyCopyable {

private:

int* i;

public:

nonTriviallyCopyable (const nonTriviallyCopyable& from)

{

/* perform non-trivial copying routine */

i = new(int(*from.i));

}

};

Deep and shallow copying is the simplest example. The gist of the problem is that by

copying the data manually, we may break the inherent behavior of the object which may rely on

the copy constructor. Any shared or unique pointer would be another great example - by simple

copying it with memcpy() we break the deal we made with that class when we used it and it

may lead to leaks or crashes.

There are many more sophisticated details the application must deal with when it

manually copies the contents of an object. C++11 standard provides in

header <type_traits> type trait std::is_trivially_copyable which ensures if a given

type satisfies the requirements of TriviallyCopyable. Referring to C++ standard, an object

satisfies requirements of TriviallyCopyable when:

A trivially copyable class is a class that:

— has no non-trivial copy constructors (12.8),

— has no non-trivial move constructors (12.8),

— has no non-trivial copy assignment operators (13.5.3, 12.8),

— has no non-trivial move assignment operators (13.5.3, 12.8), and

— has a trivial destructor (12.4).

A trivial class is a class that has a trivial default constructor (12.1) and is trivially copyable. [ Note: In particular, a trivially copyable or trivial class does not have virtual functions or virtual base classes.—end note ]

And this is how the C++ standard defines non-trivial methods:

A copy/move constructor for class X is trivial if it is not user-provided and if

— class X has no virtual functions (10.3) and no virtual base classes (10.1), and

— the constructor selected to copy/move each direct base class subobject is trivial, and

— for each non-static data member of X that is of class type (or array thereof), the constructor selected to copy/move that member is trivial;

otherwise the copy/move constructor is non-trivial.

This means that a copy or move constructor is trivial if it is not user-provided, the class has nothing virtual in it and this property holds recursively for all the members of the class and for the base class. As you can see, C++ standard and libpmemobj transactions implementation limits the possible objects type to store on persistent memory to satisfy requirements of trivial types but the layout of our objects must be taken into account.

Object layout

Object representation (layout) might differ between compilers/compiler flags/ABI. The compiler may do some layout-related optimizations and is free to shuffle order of members with same specifier type (public/protected/public). Another problem related to unknown object layout is connected to polymorphic types. Currently there is no reliable and portable way to implement vtable rebuilding after reopening the pool, polymorphic objects cannot be supported with persistent memory.

If we want to store objects on persistent memory (memory mapped files – to be precise and to follow SNIA NVM programming model), we must ensure that following casting will be always valid:

1

someType A = *reinterpret_cast<someType*>(mmap(...));

In other words, the bit representation of stored object type must be always the same and our application should be able to retrieve stored object from memory mapped file without serialization.

It is possible to ensure that a specific type satisfies above requirements. C++11 provides

another type trait std::is_standard_layout. The standard mentions that it is useful for

communicating with other languages (for creating language bindings to native C++ libraries

e.g.), and that’s why a standard-layout class has the same memory layout of the equivalent C

struct or union. A general rule is saying that standard-layout classes must have all non-static

data members with the same access control (we mentioned at the beginning of this blogpost,

that C++ compliant compiler is free to shuffle access ranges of the same class definition). When

using inheritance, only one class in the whole inheritance tree can have non-static data

members, and the first non-static data member cannot be of a base class type (this could break

aliasing rules), otherwise, it’s not a standard-layout class.

C++11 defines std::is_standard_layout as follows:

A standard-layout class is a class that:

— has no non-static data members of type non-standard-layout class (or array of such types) or reference,

— has no virtual functions (10.3) and no virtual base classes (10.1),

— has the same access control (Clause 11) for all non-static data members,

— has no non-standard-layout base classes,

— either has no non-static data members in the most derived class and at most one base class with non-static data members, or has no base classes with non-static data members, and

— has no base classes of the same type as the first non-static data member.

A standard-layout struct is a standard-layout class defined with the class-key struct or the class-key class.

A standard-layout union is a standard-layout class defined with the class-key union.

[ Note: Standard-layout classes are useful for communicating with code written in other programming languages. Their layout is specified in 9.2.—end note ]

Having discussed object layout, we may dive into another interesting problem with types possible to store on persistent memory: pointers.

Pointers

In previous sections we were quoting standard multiple times. We were describing limits of types which were safe to snapshot, copy around and which we can binary-cast without thinking of fixed-layout. But what about pointers? How does one deal with them in our objects as one comes to grips with Persistent Memory Programming Model? Let’s consider the following simple code snippet:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

class A {

int* vptr1;

int* vptr2;

}

...

int a1 = 1; /* variable on stack */

int* a2 = mmap(...); /* pointer to persistent variable */

a2 = 2;

pmem::obj::transaction::run(pop, [&](){

root->ptrA = pmem::obj::make_persistent<A>();

root->ptrA->vptr1 = *a1;

root->ptrA->vptr2 = a2;

};);

We are using libpmemobj++ transactional API. Class A does have two volatile pointers.

Our application is assigning (transactionally) two virtual addresses – one to integer residing on

stack and the second one to integer residing on persistent medium. What will happen if an

application crashes or exits after execution of the transaction and if we run application again?

Since the variable a1 was residing on stack, the old value vanished. But what with value

assigned to a2? Even if it resides on persistent medium, the volatile pointer is no longer valid

(we are not guaranteed that if we call mmap() again, it will be mapped to the same virtual

address space region). The same problem applies to variable a1 and virtual address space

pointer to it, but we wanted to underline problem with volatility of value on DRAM.

As shown in the example above, it is very important to realize that storing volatile

memory pointers in persistent memory is almost always a design error.

Using pmem::obj::persistent_ptr<> class template is safe, and it provides only way to

access specific memory area after application crash. However, pmem::obj::persistent_ptr<> type doesn’t

satisfy TriviallyCopyable requirements (because of explicitly-defined constructors). As a

result, the object with a pmem::obj::persistent_ptr<> as a member, won’t

pass std::is_trivially_copyable check. Every persistent memory programmer should

always check whether pmem::obj::persistent_ptr<> could be copied in that specific

case and if that wouldn’t cause errors and (persistent) memory leaks. One should realize

that std::is_trivially_copyable is the syntax check only and it doesn’t tests semantics.

Technically speaking, using pmem::obj::persistent_ptr<> in this context leads to

undefined behavior. There is no golden mean and since C++ standard does not fully support

persistent memory programming, we should make sure that copying pmem::obj::persistent_ptr<> is safe to use in our case.

Now we are ready to summarize all standard and programming model related

restrictions and move forward to the next subchapter.

Summary

C++11 provides a couple of features for persistent memory programmer. The most accurate type traits are:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

template <typename T>

struct std::is_pod;

template <typename T>

struct std::is_trivial;

template <typename T>

struct std::is_trivially_copyable;

template <typename T>

struct std::is_standard_layout;

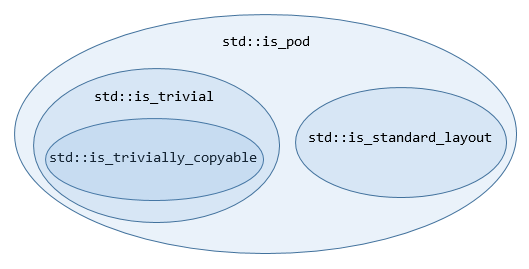

They are correlated with each other. The most general and restrictive is definition of POD type

(however, std::is_pod will be deprecated in C++20):

As we already mentioned, persistent memory-resident class must satisfy requirements of:

std::is_trivially_copyablestd::is_standard_layout

Persistent memory programmer is free to use more restrictive type traits. If we want to use

persistent pointers however, we cannot rely on type-traits and must be aware of all problems

related to copying objects with memcpy() and layout representation of objects. For Persistent

Memory Programming concept, formal description or standardization of the aforementioned

concepts and features should take place. We must be aware and deal with object

lifetime related undefined behavior.