Using Memkind in Hazelcast

This blog post is published on the Hazelcast blog as well. If interested in Hazelcast, check the other posts there too.

Introduction

The mission of the PMDK team has always been and will always be to make programming persistent memory easier for the community of software developers. One of our goals is to help simplify the integration of persistent memory into software solutions by making it transparent as possible. Adopting ground-breaking and disruptive technology creates a chasm, which is challenging to cross at first. To help with that, PMDK offers a multi-layered stack of solutions so that developers can choose a library that is the best fit for their desired level of abstraction and purpose.

Intel Optane persistent memory (PMem) can be configured in two modes: Memory Mode or App Direct Mode. In Memory Mode, the system’s DRAM behaves as a cache while PMem provides large memory capacity. When configured for Memory Mode, applications and the operating system perceive a pool of volatile memory no different than on DRAM-only systems. Use of PMem in Memory Mode is transparent to applications and the operating system, so no specific persistent memory programming is needed. When configured in App Direct Mode, however, the applications and operating system are explicitly aware that there are two types of memory on the platform, and can direct which type of data read or write is suitable for DRAM or PMem. PMDK is a suite of software libraries designed to take advantage of persistent memory when using App Direct Mode.

In this post, we will present how the cooperation between Hazelcast and the PMDK team improved Hazelcast’s overall performance with PMem. We will also showcase how to mitigate one of the most common problems with Java applications and garbage collection limitations. This post also demonstrates how an efficient use of hardware enables solutions to scale better while retaining low tail latency.

In this article, we will focus on using Persistent Memory directly, through App Direct Mode. One of the easiest ways to adopt PMem is to use it as a volatile extension of the existing memory where applications use PMem as regular memory without any intention of retaining data across power or restart cycles. The adoption barrier of integrating PMem this way is relatively minimal, but there are some important technical considerations we discuss in this post.

About Hazelcast

Hazelcast IMDG (In-Memory Data Grid) is a leading open source in-memory solution written in Java, capable of storing a large amount of data in an elastic distributed cluster with a rich set of functionality for operating on the stored data such as querying with SQL, performing distributed computations and many more. Operating entirely in the memory is the central concept of Hazelcast to guarantee that these operations are done with a low and predictable latency and with a stable throughput. Hazelcast is widely used as a caching layer, for storing web sessions, for efficient fraud detection and for many other use cases.

Working with Big Data in the Java Virtual Machine

Given that Hazelcast is written in Java, it is inherently sensitive to the unpredictability of the garbage collection (GC) algorithm used by the Java Virtual Machine. The traditional GC algorithms are famously known to put a practical limit on the usable heap size. This practical limit can manifest itself in the so-called stop-the-world GC pauses, which means the Java Virtual Machine (JVM) suspends the application threads to ensure nothing mutates the heap while certain phases of the GC algorithms are doing their job. The bigger the heap, the bigger these pauses, which may render the hosted application unresponsive, lagging or just not operating with predictable response times. This problem led the JVM vendors to research and implement a new generation of the GC algorithms, the concurrent GC algorithms, such as the C4 (Azul), ZGC (Oracle) and Shenandoah (Red Hat). These GC algorithms all focus on eliminating or limiting the aforementioned pauses in order to be able to manage huge heaps, up to terabytes in size. This is already a big enough heap for Hazelcast, but these algorithms have their trade-offs as well. The threads of the concurrent GC algorithms run concurrently with the application threads and can steal precious resources from them. Given that freeing up the unused memory is done while the application threads are running - therefore, the application threads allocate concurrently - it is possible that even these clever GC algorithms are unable to keep up with the pace of the allocations and need to employ their so-called failure modes, which is a well-controlled form of impacting the application to get the control back over the allocation/reclamation dynamics. As the worst case option, these algorithms may need to suspend application threads as well.

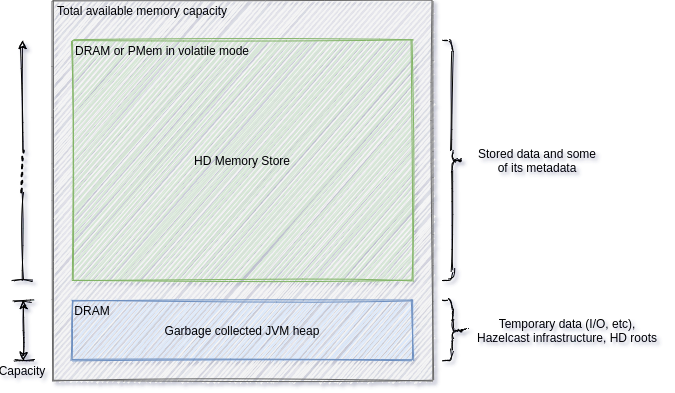

To overcome the above limitations with the GC, and to guarantee the low and predictable response times, Hazelcast improved its enterprise offering years ago by implementing an in-memory storage that stores the data outside of the Java heap. This feature is named High-Density Memory Storage (HDMS or just HD), also known as native or off-heap storage. While there is still GC involved, the data Hazelcast stores in its HD storage is not subject to the GC, therefore, that data can be very big in size without running into the problems of the GC mentioned above. For more details on HD, refer to the blog post introducing HD.

First launched in 2019, Intel Optane persistent Memory offers DIMM-compatible non-volatile memory-modules. While the biggest breakthrough of these modules is their persistent capability, using them in a volatile App Direct Mode is also attractive in some use cases. These modules are available with greater capacities than that of DRAM DIMMs. Therefore, the total achievable capacity is bigger than with DRAM modules alone, while the modules operate with near-DRAM performance, at a lower cost per gigabyte. These advantages make the Intel Optane PMem modules a good fit for Hazelcast and after some research, Hazelcast 4.0 added support for these persistent memory modules - in addition to DRAM - as its HD backend. The initial implementation in 4.0 used libvmem for using Intel Optane persistent memory modules in volatile App Direct Mode. Since then, Memkind became the go-to library for using the PMem in volatile mode, therefore, Hazelcast dropped libvmem and replaced it with Memkind in its 4.1 version.

Integration with Memkind

Memkind is a library for managing multiple types of memory (e.g., DRAM, MCDRAM, PMem), with different performance characteristics. This solution enables applications to use persistent memory as the capacity tier for memory resident data. In heterogeneous memory systems, where two or more memory types are present, memkind is a solution that helps applications to overcome the challenge of managing complex memory architectures.

In memkind, memory is managed as independent heaps, called memory kinds.

Hazelcast takes advantage of both solutions libmemkind provides for using PMem. The PMEM kind let’s the user application allocate from the PMem medium if it is mounted with a DAX-aware file system. The KMEM-DAX mode combines the advantages of the Linux kernel’s KMEM feature and the direct access (DAX) capabilities of PMem by transparently allocating PMem memory from the system memory consisted of DRAM and PMem backed regions after preliminary configuration of PMem. The two modes will be discussed in detail later.

To leverage the advanced heap management offered by Memkind, Hazelcast needed to

build a Java Native Interface (JNI) bridge. Integrating Memkind was a straightforward task

since Hazelcast’s HD memory manager interacts with the memory allocators through a malloc-like

internal abstraction with an API that is similar to standard memory allocation API’s.

The notable difference with Memkind is that the caller should define a kind for an allocation,

and also may define the kind when freeing or reallocating a memory block. If the kind is not defined,

Memkind detects which kind should be used. This kind detection feature turned out to be a very

useful feature for Hazelcast, even though at the time of writing this post Hazelcast exclusively

use the PMEM or the MEMKIND_DAX_KMEM_ALL kinds.

Looking forward, this could help Hazelcast build a tiered HD storage feature, for example with DRAM and PMem tiers, to take advantage of the heterogeneous platform architectures. Implementing such a tiered storage is inherently difficult with heterogeneous memory allocators, since allocating, freeing and reallocating a memory block has to use the same allocator. Otherwise, various problems may occur potentially crashing the application. To deal with this problem, one can track the allocator used for every memory block. The disadvantage of this approach is a significant increase of the fragmentation. Since memkind internally tracks the dedicated memory kind of a given object from the allocation metadata, it can detect the kind for every object allocated with the library. This is a great help for the applications dealing with heterogeneous memory resources as memkind eliminates the aforementioned problem entirely. To learn more on kind detection, please see this post.

The collaboration between the PMDK team and Hazelcast helped streamline PMem integration into the

High-Density Memory Store. The Hazelcast team uses the memkind library

to explicitly allocate PMem space. When using the FS-DAX base memory kind, the Hazelcast team analyzed

memkind performance in the context of shutdown times and found the bottleneck in the form

of a punch hole operation when destroying the file-based memory kind. Punch hole operation is

used to deallocate blocks presented on filesystem and is called during deallocating memory using

memkind API so the underlying pages could be returned to the OS. The PMDK team suggested using

the mechanism MEMKIND_HOG_MEMORY that controls the behavior of memkind in this regard,

reducing the amount of memory returned to the system, and instead allows the allocator to directly

reuse the already allocated memory pages. With this change the punch-hole operation was not called during

the free operation. Subsequently, we discovered that the punch hole operation was no longer required

when destroying a PMEM memory kind, which allowed us to eliminate this operation

for even greater performance gains, resulting in further reduction of the shutdown times experienced by Hazelcast.

As another result of the teams collaboration the next release of libmemkind will be improved by providing a method to verify if the path used to create a PMem memory kind point on the DAX-aware filesystem, which previously was possible only by using additional dependency like libpmem. With this change the memkind library will become an even more standalone library.

Unified PMEM heap

As mentioned before, Hazelcast uses the PMEM and the MEMKIND_DAX_KMEM_ALL kinds.

The latter is straightforward to use as the kind defines a single heap even on multi-socket machines.

On the other hand, the file-system DAX mode that the PMEM kind is built on is a bit different.

Unified heap in the FS-DAX mode

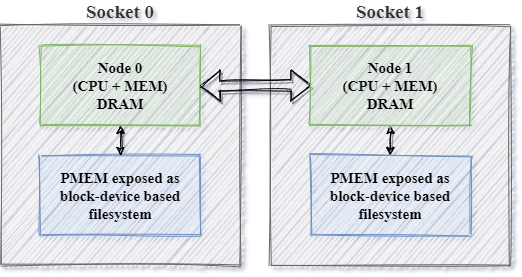

On multi-socket systems there could be many persistent memory devices even if the modules are interleaved, one device for every socket. Figure 2 presents this filesystem-based solution which memkind uses to support the PMem devices. Each PMem device is visible to the Operating System as a block device based on the DAX-aware filesystem. The block device can be mounted in various possible locations; therefore, the user must create a PMEM memory kind for a defined path. In this mode, to utilize all PMem memory available in the system, the application must make separated heaps for each socket (for each PMem device). Besides managing the heaps separately, the application is also responsible for making the allocations NUMA-aware.

Applications that don’t want to deal with managing separate heaps can use software RAID(see LVM with persistent memory and Storage Redundancy with Intel Optane) to create a single mount point and one PMEM kind for the multiple devices. With this option the unification is done at the OS level. This has the consequence that the application can’t control whether it accesses local or remote persistent memory.

This realization inspired Hazelcast to implement its own heap unification with round-robin and NUMA-aware allocation strategies. The round-robin strategy ensures every allocation is done from a different PMEM kind than the last one and is a best-effort approach for achieving a similar ratio of local persistent memory accesses on every thread. Assuming fix-sized allocations, this strategy makes the ratio of the local persistent memory access inversely correlated with the number of the sockets in the system. With two sockets the ratio is 50%, with 4 sockets it is 25% and so on. This strategy is sufficient for many use cases, and is used as the default strategy. In some other cases involving more persistent memory access - such as using Hazelcast to store bigger entries, performing computations on multiple entries -, the remote accesses incur a noticeable performance cost. In order to make all persistent memory accesses local, one should consider using the NUMA-aware strategy. This strategy pins every Hazelcast operation thread to a single NUMA node and makes every allocation - thus access - done in a PMEM kind that is local to the allocator thread. In the mentioned cases this helps in improving the response times by lowering the latency of the LLC misses. To learn how to set the allocation strategy, please refer to the Hazelcast reference manual.

These strategies focus on the performance of the persistent memory access, but being able to utilize the whole available capacity is just as important. The above allocation strategies implement “allocation overflowing”. If the PMEM kind chosen by the used allocation strategy can’t satisfy the allocation request, an attempt is made to allocate from the rest of the PMEM kinds before reporting out of memory to the allocator. This ensures that the available PMem capacity can be utilized even in the undesired case when accesses of the PMEM kinds are out of balance.

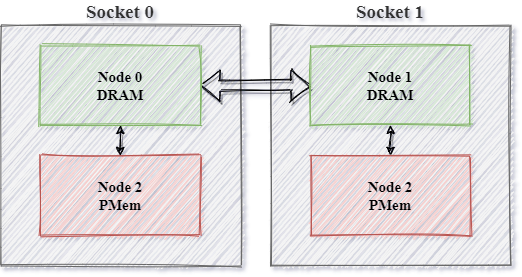

Unified heap in the KMEM-DAX mode

Besides using software RAID, applications running on Linux kernel 5.1 or higher have a second option for solving heap unification at the operating system level. With this option, the PMem devices are exposed to the Operating Systems layer as separate memory-only NUMA Nodes, as presented in Figure 3. Handling this mode in memkind is simplified – there is no need to create a memory kind explicitly. Memkind provides the memory kind mentioned earlier in the form of a predefined object. This type of abstraction allows accessing memory from both NUMA Nodes using one heap. The static memory kind is also NUMA aware. The PMem memory will come first from the NUMA node with the smallest distance from the CPU of the calling thread, and if the memory from the local PMem NUMA Node doesn’t have memory to fulfill the request, it will switch to the remote PMem NUMA Node. This heap unification is a convenient mechanism to limit necessary changes to include PMem.

Thoughts on the performance of Intel Optane persistent memory

In the above sections we described the modes offered by memkind for allocating volatile memory backed by PMem and how Hazelcast builds on these modes. In the following we share some thoughts on the performance of PMem in general and some of the key findings of the Hazelcast team from benchmarking Intel Optane persistent memory in a distributed environment.

As discussed in one of the previous posts on the PMDK blog, PMem is a new tier between Memory and storage. Apart from the data persistence and previously mentioned big capacity, the CPU can access the data directly. Access to information in the physical medium is provided with cache-line granularity. Besides memory capacity, PMem fulfills the gap between DRAM and storage in terms of latency. It provides an asymmetric performance (see section 12.2 and Basic Performance Measurements) depending on the type of access operation reading/write and characteristics of access sequentially/random.

Performance impact for remote NUMA access for Intel Optane persistent memory is much larger

compared to DRAM (see section 5.4). To achieve the best performance, we need to limit

the remote connection between sockets and focus on local memory access in the context

of Non-Uniform Memory Access (NUMA). The previously mentioned API provided by memkind

is NUMA-aware. It means that in the case of allocation to PMem using MEMKIND_DAX_KMEM,

memory kind results in allocating memory from closest PMem to CPU, which requests an allocation,

solving this performance problem transparently to the application.

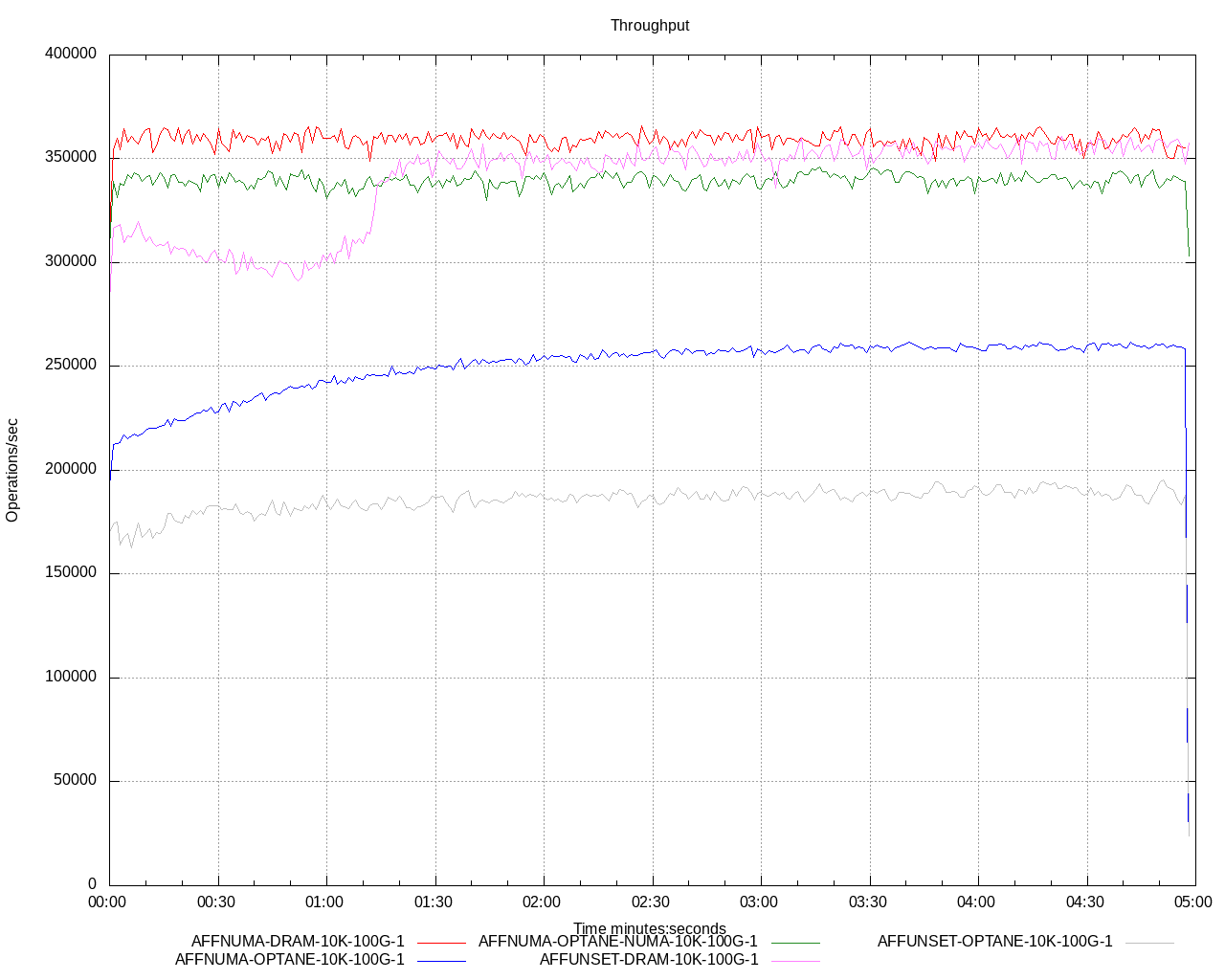

The performance of these PMem modules is in between the performance of DRAM modules and storage devices. The bandwidth of Intel Optane persistent memory is lower than the bandwidth of the DRAM modules, while their access time is greater. This would make some think that PMem compared to DRAM is a poor choice when it comes to performance. Based on Hazelcast’s tests, this is not necessarily the case. Despite the slight performance handicap of the PMem devices, in many use cases Hazelcast recorded performance results with PMem very similar to the results with DRAM. There are multiple reasons for this. Since the persistent memory accesses are transparently cached in the CPU cache layers just like the DRAM accesses are cached, the cache-locality techniques used to speed up DRAM accesses work just as well for PMem. Hazelcast uses these techniques to exchange DRAM and PMem accesses to cache hits where it is possible making it irrelevant if the used cache lines are backed by DRAM or by Intel Optane persistent memory. Another reason lies in the fact that Hazelcast is a distributed system working with many networking communications that involve serialization, in-memory copying, and internally, inter-thread communication. There are also hiccups added by the JVM - just like GC pauses - and by the OS. All of this incurs performance costs that are potentially in a higher range than the extra cost of accessing PMem compared to accessing DRAM. In other words, Intel Optane persistent memory’s features can help achieve similar performance compared to DRAM when operating in a distributed environment. Hazelcast’s main finding for Intel Optane persistent memory achieving performance parity with DRAM was paying attention to the NUMA-locality. Figure 4 illustrates the potential gain that can be achieved by NUMA-local Intel Optane Persistent Memory accesses in FS-DAX mode. The chart compares the throughput of a single Hazelcast member with the same caching workload, but with different settings. The benchmark used for producing the chart executed two operations: get and put operations in Hazelcast IMap (Hazelcast’s key-value data structure), both with 50% probability to read and update the values. The legend encodes these settings as described below:

- AFFUNSET/AFFNUMA: It tells if thread affinity was set or not set for Hazelcast’s worker threads. AFFUNSET means the scheduler was free to run the worker threads on any CPU it wanted, while AFFNUMA means all worker threads were bound to a single NUMA node’s CPUs, balanced evenly between the two NUMA nodes of the dual-socket test machine.

- DRAM/OPTANE/OPTANE-NUMA: Whether the data stored by Hazelcast is on DRAM or on Optane. OPTANE stands for the previously described round-robin allocation strategy, while OPTANE-NUMA means that the NUMA-aware allocation strategy.

- 10K: The size of the entries used in the test.

- 100G: The total data size the Hazelcast member operates with.

- 1: The iteration number of the test with the given setup. Always one in this case.

The chart shows the drastic change in Hazelcast’s throughput just by changing the NUMA-local Intel Optane persistent memory accesses from 50% (blue line) to 100% (green line). It also shows that there is no such big difference in the case of DRAM (pink and red lines). Besides the less sensitivity to the NUMA-locality of DRAM, the other reason is that the operating system can do it’s best to keep the data and the code using it on the same NUMA node. This is a nice attribute of the KMEM-DAX mode too, the pages backed by PMem used in KMEM-DAX mode are subject to the regular memory placement policies of the Linux kernel. This is not the case if the FS-DAX mode is used, because in that mode the application’s PMem access pattern is totally opaque to the operating system as managing the heap backed by PMem is entirely done in the user space.

Summary

To conclude, in this blog post, we presented a story of leveraging the capacity aspect of Intel Optane persistent memory in an existing software product from Hazelcast. We brought this solution into fruition with the aid of one of the PMDK libraries - memkind. By extending Hazelcast’s existing solution for a garbage collector’s problem, we’ve enabled the software to leverage heterogeneous memory platforms. In the end, we’ve crafted a solution that offers predictable latency and larger capacities of memory than possible before, all with a lower cost for the end user.

Article written together by Zoltán Baranyi and Michal Biesek.