Libpmemobj-cpp - lessons learned

Introduction

We’ve been working on C++ bindings for libpmemobj since around 2016 - see our very first tutorial for libpmemobj-cpp. We’ve come a long way since then. A lot has changed - we’ve gained more experience and knowledge, added new features, fixed quite a few bugs, and created at least half a dozen new containers. It’s fair to state this product is now far more mature and well-developed. Over time, we’ve learned at least several lessons about designing and overcoming issues in C++ applications for persistent memory. We want to share them with you to learn from our mistakes and not waste any time.

Design problems

Designing efficient concurrent algorithms for persistent memory is a challenging task. Actually, this is one of the reasons why we introduced libpmemobj-cpp in the first place. We wanted to do the hard work once, test it as much as possible, and give people reliable, efficient, ready-to-use solutions. We describe below only a few of our problems, which we believe might benefit for a broader audience.

Optimize number of allocations!

Lots of allocations on pmem may ruin performance. It seems like an obvious statement, but

it’s easy to overlook this issue. One badly placed allocation (e.g., in critical

code path), and we end up with low performance. Unfortunately, inserting a new node in

pmem::obj::concurrent_hash_map is associated with multiple allocations.

When we were thinking about the next container to implement, we chose radix tree structure.

It is a great fit for pmem, because it requires a minimal number of allocations, no tree

re-balancing, and it is sorted but requires no key comparisons. We realized

pmem::obj::experimental::radix_tree can be optimized even further. To store keys or

values of variable length, string (pmem::obj::string to be precise) is a natural

choice. Each such string means an extra allocation for the variable data.

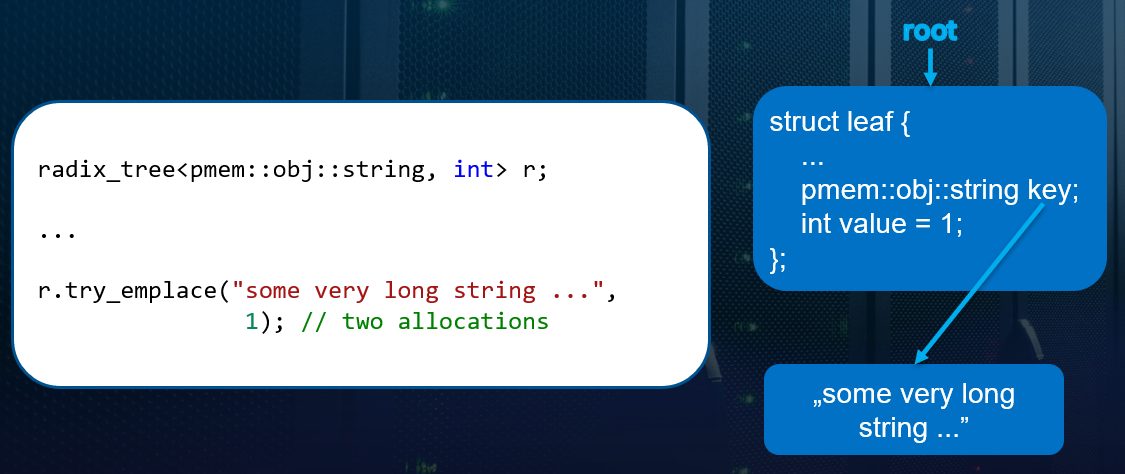

- Figure 1. Radix_tree with string - one extra allocation.

As you can see in Figure 1. - there’s one allocation for the radix_tree node

and one extra for the string data itself. To overcome this, we proposed an

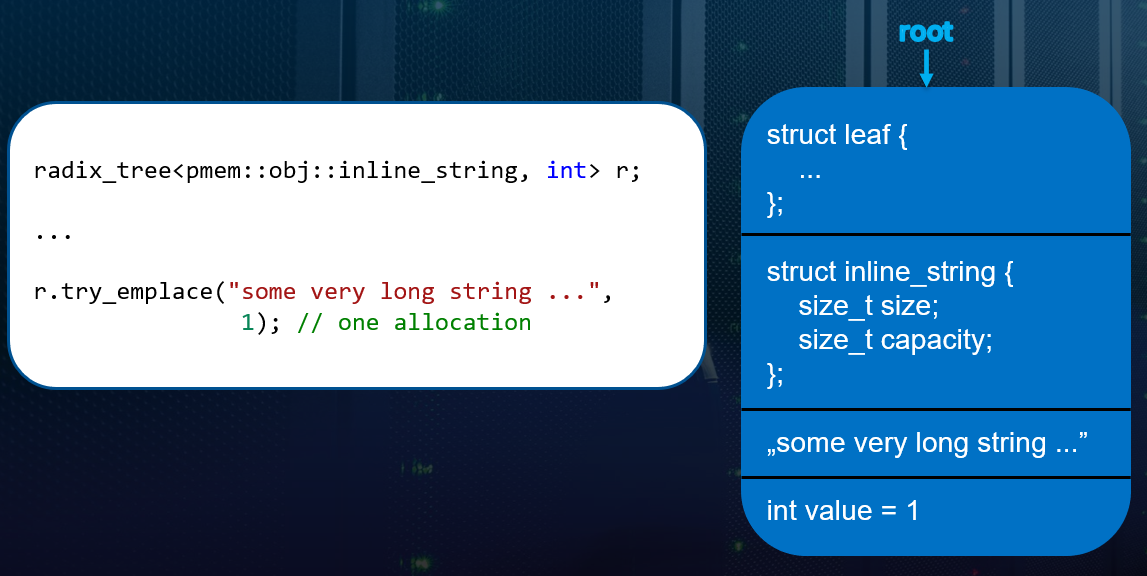

inline_string, which keeps the actual data within the same allocation. In Figure 2.

below, you can see that all the data is held together: metadata, key

(right next to inline_string structure), and value.

- Figure 2. Radix_tree with inline_string - no extra allocations.

We can see it’s all done in one, slightly bigger allocation. There’s a drawback! When it comes to updating the string data, and the value is longer than the existing string allocation - the whole node has to be re-allocated.

Using per-thread data

Very recently, we’ve described (in the “Concurrency considerations” blog post) our approach to ensure data consistency. It’s a very challenging task, especially if you consider concurrent modifications within a container full of records, with multiple threads accessing/modifying the same structure. Read the whole post for details, but long story short - per-thread data (implemented in libpmemobj-cpp as enumerable_thread_specific) can save you from data consistency issues.

Keeping locks on pmem is not a good idea

Since we keep all data for our application on persistent memory, one might think we should

do that as well with locks. That’s the wrong way. Each lock and unlock operation might end up

with a write to pmem. Even though we do not explicitly flush lock cache lines, they are

invalidated when a lock is accessed from a different core as part of ensuring coherency.

An additional write to pmem is, of course, undesired and limits the scalability of our data

structures. The solution is to move locks to DRAM instead. Only pointers to these locks

are held on persistent memory. Mentioned extra writes are less costly to DRAM than to pmem.

Currently, within our library, it is only possible with concurrent_hash_map. There are

two approaches, how we can use these locks:

-

The first one is to keep per-element locks. It’s a good fit when you store large elements. With too many small objects, this approach may quickly exhaust available memory.

-

The second solution is to use sharding instead of per-element locks. Data can be divided into multiple single-threaded buckets, each protected by a lock. This way will provide a short waiting time on locks and good performance, but only with a uniform distribution of elements and a big enough number of buckets. In practice, this can be easily implemented, e.g., in unsorted data structures. It also means lower memory demand because of the lower number of locked objects.

Lazy rehashing

A hash table, from time to time, has to perform a full rehashing of existing entries.

In a concurrent environment, this task is even more demanding and may require locking

the entire structure. With that approach, you will observe latency spikes in moments

of such rehashing, slowing down each new write to the structure. In our

concurrent_hash_map we introduced a “lazy rehashing” solution, based on the paper

“Per-bucket concurrent rehashing algorithms”. When rehashing

is required, the number of buckets is doubled. Later, while accessing (in any way)

an element, it may be moved into some of the new buckets or may stay in place. With

this algorithm, rehashing happens one element at a time, not all at once. No global

locks are taken, only per bucket ones. Access is blocked to elements in the same

bucket, so the whole process does not significantly impact concurrency or structure’s

performance. If you’re curious, you can found all the algorithm’s details in the

linked article.

Layout compatibility

By publishing a stable release of libpmemobj-cpp, we committed to a stable on-media layout.

From that point, we try and still promise that. We had a small hiccup on the way (in PMDK)

with pools compatibility, but we’ve managed to fix that with the help of a tool now called

pmdk-convert. Right now, we’ve learned our lesson - we try to make the

layout extensible, but we know that we don’t know everything. That’s why, keeping in mind

future improvements, we save up some space for extensions in each structure. We’ve also

introduced a mechanism for checking the compatibility - a feature_flags. Each time a data

structure, which implements feature flags, is used, we check it for compatibility. For example,

in concurrent_hash_map on each initialization, we call check_incompat_features() method,

and it throws an exception in case of any flags discrepancies. These flags can be used,

for example, to assert key/value size(s) or check the support of a certain feature.

Implementation guidelines

Over time we encountered some issues failing our Continuous Integration testing scripts and example apps. Sometimes though, something slipped our tests and CI process, and was found by our users. We strive to make our tests as comprehensive as we can, but no process is perfect. Years of experience provided us with small but good practices when designing a new container or a method. We’ve listed these in a practical guide for contributors, which we follow every day. The list is, naturally, not complete - we always look for something to improve.

Summary

We hope it was helpful to read about all these challenges. You can learn from our mistakes, not repeat them, and, hopefully, make good software using persistent memory. If you’d like to learn more, we’ve shared some of these issues (and solutions) in the 2021 PMDK Summit in a presentation titled “State of Pmemkv” . Jump into that summit’s videos for more info about our projects. And don’t forget we’re open source. Do you have ideas to improve our algorithms, extend this library, or just want to make a suggestion? Please share - file an issue or simply open a pull request with your tweaks.